Have you ever wondered how mountains are made? Sure everyone has probably thought about how tectonic plates pushed together to form mountain ranges, but what’s the difference between a hill and a mountain? One is taller, but the line has to be drawn somewhere. Is Mount Rushmore a “real” mountain, or is it just a mound? Perhaps our classification system is flawed.

While there are various methods for determining what constitutes a mountain such as percent slope, height, and elevation, critical theory can also aid in this analysis. When we make a distinction on what is a mountain, we in turn establish what isn’t a mountain. You see the thing is, we know what a mountain is. We know what it looks like, we know where they are, but sometimes data and information can get in the way. Colorado is at a higher elevation than Tuscaloosa, but the entire state isn’t one big mountain. The Grand Canyon has a very high percent slope, but we know it isn’t a mountain either (Hint: it’s a canyon). The Badlands in South Dakota have a fair amount of slope, and altitude, but not much height compared to somewhere in the Smoky Mountains.

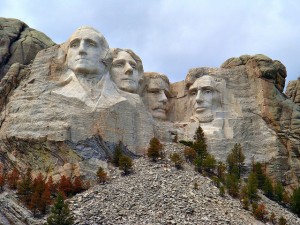

Another issue when determining how tall a feature must be to be considered a mountain is where you’re starting your measurement. Mountains are measured as height above mean sea level. Take Mount Rushmore for instance. The “mountain” stands 5,725 ft above sea level, but from “base” to peak, it is only around 500 ft tall. My argument is not that Mount Rushmore is not a mountain, but I do wonder if it would be considered a mountain if it was located in an area with a generally lower elevation. Mount Rushmore is in the Black Hills region of South Dakota, but it would probably sound silly if the memorial for four U.S. presidents was entitled “Rushmore Hill.” A mountain sounds important, strong, and independent, which is arguably what we admire about those presidents. A hill sounds like something you avoid on your run. It’s common and not too difficult to conquer. So does a sort of cultural standard outweigh facts and statistics? Does the current classification and measurement practice for mountains represent what a “real” mountain is?

The real question is how do we choose to define a mountain? Do we take into account all of these questions I’ve raised? That’s the tricky thing about defining things. Mount Rushmore may be a mountain. It may not. What I’m saying is that what a mountain “is” is constructed by those who made the category. As we classify the world around us, we create further complexities because some things are left out and others are included within a category, but this is how we understand the world around us.

Photo by: AmeliaTWU. Mount Rushmore National Memorial

Flickr: Creative Commons 2.0